Connecting...

This is a quick preview of the lesson. For full access, please Log In or Sign up.

For more information, please see full course syllabus of Multivariable Calculus

For more information, please see full course syllabus of Multivariable Calculus

Multivariable Calculus Tangent Plane

Lecture Description

In this lesson, we are going to talk about a very, very important topic called the tangent plane and it is exactly what you think it is. If you have a curve in space and you have some line, like in calculus when you did the derivative, you had the tangent to that curve - this is the analog, the next level up. If you have some surface in space, there is going to be some plane that is actually going to be tangent to it. It is going to touch the surface at some point. We are going to devise a way using the gradient to come up with an equation for that tangent plane.

Bookmark & Share

Embed

Share this knowledge with your friends!

Copy & Paste this embed code into your website’s HTML

Please ensure that your website editor is in text mode when you paste the code.(In Wordpress, the mode button is on the top right corner.)

×

Since this lesson is not free, only the preview will appear on your website.

- - Allow users to view the embedded video in full-size.

Next Lecture

Previous Lecture

Answer Engine

Answer Engine

1 answer

Fri Aug 18, 2017 3:39 AM

Post by Ivan Burov on July 26, 2017

Dear Professor,

Does it matter that the equation given in the example is equal to 10? Or because it has no impact on differentiation it can be any constant? What is the physical meaning of 10 then?

Thanks!

Ivan

1 answer

Thu Jul 6, 2017 4:56 AM

Post by Tom Beatty on July 4, 2017

What am I missing in the last example: the pt (1,2) doesn't appear to lie on the curve f = xy^2+x^3=10?

f(1,2) = 1*2^2 + 1^3 = 5 not equal to 10

1 answer

Mon Jan 11, 2016 1:23 AM

Post by Jamal Tischler on January 8, 2016

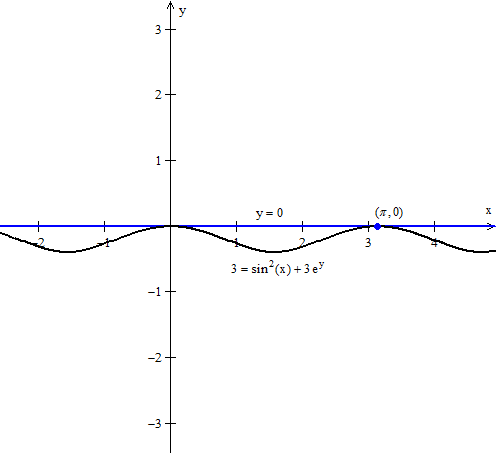

I made a graph of a function in 2-space to show the gradient vector and the tangent line to the graph (using Desmos). Grab the blue dot and move it along the graph(only that way it will work), the purple segment will be the gradient vector.

https://www.desmos.com/calculator/foyfotfvjn

But why is it that the gradient that consist of all the partial derivatives will always be perpendicular to the curve ?

1 answer

Thu Nov 12, 2015 6:58 PM

Post by Ahmed Alzayer on November 12, 2015

Good Evening,

I have a problem that states the following:

Find an equation of the tangent plane to the graph of the given equation at the indicated point.

xy + yz + zx = 7 (1,-3,-5)

when I plug that point into the equation, it is not satisfied which means that point is

not on the plane, I thought that the given point has to be on the plane to work out the problem, can you please

clarify if there is something wrong with the given problem?

1 answer

Sat Oct 10, 2015 7:52 PM

Post by Hen McGibbons on October 10, 2015

My teacher derived the tangent plane using a taylor series. Is this another way of deriving the tangent plane using vectors? I'm assuming the way my teacher taught me can only be used for 2 space, and I'm thinking that this way can be used for any number of dimensions.

1 answer

Thu Jan 8, 2015 1:54 AM

Post by owais khan on January 6, 2015

in example 2, you made x~ = (x,y) why do you in some cases like example 1 make x~ = (x,y,z). ???

2 answers

Last reply by: Josh Winfield

Wed Feb 6, 2013 3:51 AM

Post by Josh Winfield on February 6, 2013

I always pause the video and attempt the example before watching you go through it.

This time i was way of mark with Example 2!

I saw in the question you wanted the Tangent line. So i thought whats the parametric representation of a line?

L=(P)+t(a)

P = Point of the line

a= direction Vector

I took P to = (1,2) given in the question and:

a to = the gradf(P) the direction Vector

and i got L= (1,2)+t(7,4)

L= (1+7t, 2+4t)

I clearly see that my approach is incorrect but where did i go wrong in what a thought was a logical approach???

One of the reasons i didn't think of x.n=p.n is because i thought this was a Plane equation, not a line equation?